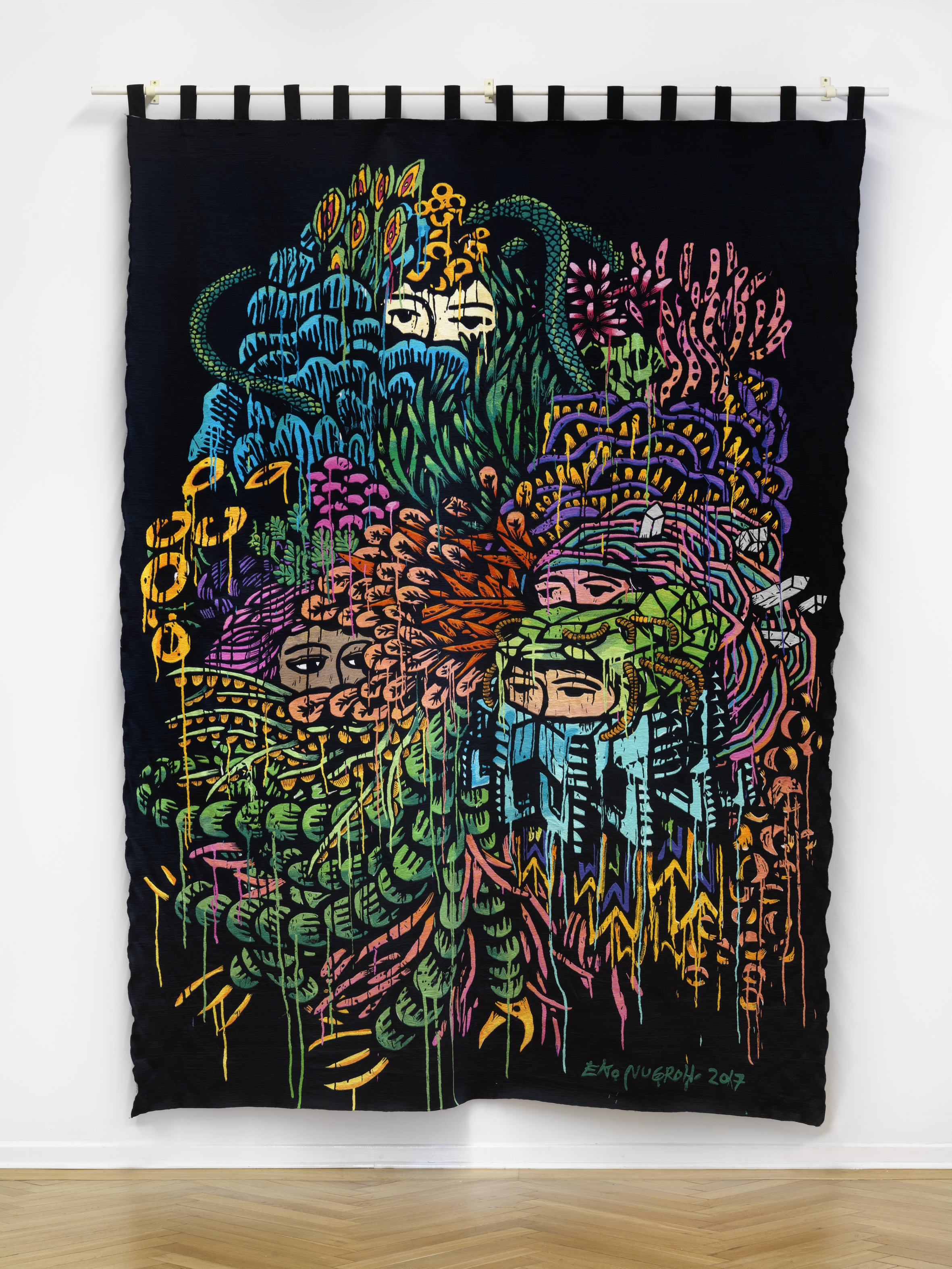

The Artistic Genius of Eko Nugroho

Photo courtesy of Arndt Art Agency

One of the most acclaimed contemporary artists in Indonesia at the moment, Eko Nugroho not only has a profound impact on the local art scene, his colorful, critical and at times humorous works have also entered the global stage at major international art exhibitions and fairs.

Eko’s second solo exhibition in Germany, "Plastic Democracy," which will run until Aug. 31 at Arndt Art Agency (A3) in Berlin, showcases 15 artworks that speak about the trials and tribulations of Indonesia's transition into one of the world's biggest democracies.

Matthias Arndt. (Photo courtesy of Bernd Borchardt)

Matthias Arndt, the founder of Arndt Fine Art and A3 and a contemporary art expert with almost 25 years of experience running a successful gallery business in Berlin, Zurich, New York and Singapore, spoke to the Jakarta Globe about the appeal of Eko’s artistic oeuvre and his role in the Indonesian contemporary art scene.

When was the first time you came across Eko Nugroho and his artworks?

In 2011, on my way to Australia, I visited the first edition of Art Stage Singapore and had my first major encounter with Southeast Asian art. Although I considered myself an expert in international contemporary art, this was a challenging experience. Having had no criteria to contextualize the very strong visual language of the mainly Indonesian and Malaysian contemporary art that I saw, I could only follow my gut feeling and my professional instinct for quality. My curiosity led me to my first research trip to Indonesia shortly thereafter. During this period I met many major artists whom I later worked with, such as Entang Wiharso, Mella Jaarsma, Arin Dwihartanto Sunyaro, Christine Ay Tjoe, Handiwirman Saputra Jumaldi Alfi and Eko Nugroho.

Photo courtesy of Arndt Art Agency

What made you decide to show Eko's works in your gallery in Berlin — now already for the second time?

We first approached the topic with the curated group exhibition "ASIA: Looking South" that included artists from all over Southeast Asia, including the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Indonesia, representing the largest group of artists from the area. It took time to identify the leading figures of each art region. With Eko, I felt an immediate connection to his work. He held his first solo exhibition with us in Berlin in 2012. This was followed by solo presentations in Berlin by Entang Wiharso and Agus Suwage.

Although the German and Western audience reacted very positively, we felt that if we were to implement Eko and the other artists’ practices in a more sustainable way, on an equal playing field with new Western trends in art, we need to provide audiences with a context to better understand Indonesian art. So in 2013, we published "SIP! Indonesian Art Today," curated by Enin Supriyanto, with renowned German publisher DISTANZ to accompany two major exhibitions in Berlin and Singapore.

In the meantime, we have transformed our business model from a commercial gallery – Arndt Fine Art – into an art agency, Arndt Art Agency (A3). We accompanied Eko’s career by promoting his artwork in many international venues, museums and curated exhibitions and collections. We've seen his work at Art Basel in Hong Kong, the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, the Samstag Museum and the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide and the Frankfurter Kunstverein in Frankfurt and many others. But these delayed Eko’s second Berlin exhibition "Plastic Democracy," which only recently opened at A3. Eko worked on this project for almost three years.

What do you think is most appealing about Eko's artworks, also to the German audience?

Eko combines both technical skills and conceptual depth in a masterful way. This combination fascinated the European audience instantly. With his direct visual language, deriving from pop and street-art influences, Eko does not shy away from addressing major issues at the forefront of Indonesian society, but also topics relevant to many communities around the world – including the so-called "First World." Eko Nugroho, like many of his fellow Indonesian artists, stays connected and committed to his community. His art is engaged and he shares some of his commercial success with younger artists, supporting their work through his merchandise label "DGTMB" as well as running his major studio operations and tapestry workshop that employ large teams. His tapestries, or "manual embroideries" as he calls it, not only provide work to many textile workers who otherwise would be unemployed due to the rise of new computer-generated technologies, but also translate traditional crafts and folk elements into today’s contemporary Indonesian art and thus, into the universal language of contemporary art. Western audiences enjoy and embrace this level of engagement with art that is connected rather than detached from its viewers and society. Eko’s work expresses its surroundings unapologetically. Eko is also simply a genius in his use of color, material and meaning in his paintings, drawings, sculptures, embroideries and installations.

Photo courtesy of Arndt Art Agency

Why did you venture into Southeast Asia?

The art world is a global business. Coming to Indonesia, and then the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand and finally, Australia, as much as I was excited about the depth and quality of art coming from Southeast Asia and the Pacific region, I also realized how little the Western world, Germany, Europe, the US, Australia, knew about this region. And more importantly, what they did not know and could not contextualize, and how Western collectors, foundations, media, and museums did not acknowledge or interact with this region.

Speaking more generally, how would you rate the contemporary art scene in Indonesia and Eko's role in it?

The art scene in Indonesia can be considered as one of the most dynamic in Southeast Asia. It draws on a long tradition of contemporary artistic practice that began with the modernist movement in the 1950s. Symptomatic of the Indonesian art landscape, many artists based in the artistic hub of Yogyakarta don't only run their own studios but also act as their own promoters. Artists like Jumaldi Alfi, Handiwirman Saputra, Putu Sutawijayam and Eko, among others, engage with their local communities. They actively organize public talks, conferences, and in the absence of state-run museums, establish artist-run spaces as platforms to show their work and support their peers.

In the absence of state museums, the private sector is the main component of the arts industry in Indonesia. There are many major private collections in Indonesia and the neighboring region that support the arts. There is also a range of artist-run spaces and initiatives in Yogyakarta that I visited on my recent tour.

I was fortunate to visit Entang Wiharso’s Black Goat Studios and Eko’s studio, while also seeing Eko’s stunning project, the "Fight for Rice" DGTMB pop-up shop. These initiatives are an example of how the more successful and experienced Indonesian artists are sharing and supporting the next generation. The shop and label were established to assist local Yogyakarta artists to fund their work – giving them "a rice job."

Visit www.arndtfineart.com and www.arndtartagency.com for more information.

This article was first published on www.jakartaglobe.id on May 28, 2018.